History Teaches . . . We Can Fight Poverty - and Defeat It

The Terrible Big Bill, and its Alternatives

This past week, the biggest U.S. news was the passage by the Senate, by 1 vote (despite a faux anguished Senator Lisa Murkowski, a faux old-fashioned Republican with faux values and a long history of faux courage in the face of party and presidential pressure), of the omnibus bill largely designed and richly desired by the Trump administration. The bill was then passed a second time (affirming the Senate version, which was not a foregone conclusion) by the House of Representatives, including by a murder of “deficit hawks” turned lovers of tax relief for rich people, crows picking over the scavenged carcass of our social welfare state and democracy.

Below is a review of some of the bill’s major features, and then an alternate way of thinking about the whole problem of (extreme) poverty in a society that produces enormous wealth and an historically high number of very-wealthy people. This latter is based on years of research I did on what today we would call a guaranteed income but which has gone by many other names - a minimum income, basic income, negative income tax, etc. All of these are ways of acknowledging the distortions in the labor market and (if you will) the wealth market, the distribution of wealth in a society that generates huge returns thanks to technology and needs to create some mechanism of getting those returns out to the majority of people — when we lack the power to negotiate for them directly with the people who employ us, and even, thanks to the way law and policy are tilted, to organize together into labor unions or community organizations to demand a more fair or sustainable portion of the wealth.

About the bill: Unlike many earlier pieces of legislation of this kind — giveaways to the richest among us and thievings of the wellbeing of the poorest — that were presented as in poor people’s best interests, there was little such pretense in this Big Bill. No Republican claimed that cuts in the amount of money the national government passes on to the states to fund the Medicaid program, which is the most important single source of health insurance for children and, along with Medicare, for disabled people, will lead to better outcomes for them.

As a report by the Center for American Progress and the ARC put it: The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the [bill] will cut federal spending on Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) benefits by $1.02 trillion, due in part to eliminating at least 10.5 million people from the programs by 2034. With new federal limits on Medicaid eligibility likely increasing the number of uninsured, along with other provisions that restrict states’ ability to raise revenue to fund their Medicaid programs, states will have to reevaluate their budgets to either supplement the spending or cut services. Research shows that when federal funding for Medicaid decreases, states tend to cut optional benefits such as home- and community-based (HCBS) [which are critically important in helping disabled people live at home and not in instituions] first. It is nearly impossible to carve out a specific population, such as disabled people or elderly people, because the cuts to Medicaid funding will affect everyone due to hospital closures and health care workforce layoffs.

There was a little games-playing about whether the new work requirements were really about work or, as people who have studied poverty and anti-poverty programs in the United States for many years (I started at an anti-poverty Select Committee of the U.S. House as a 19-year-old intern and am now a 59-year-old scholar) would generally consider them, a form of “bureaucratic disentitlement” through which government eligibility requirements themselves are so onerous or confusing that people wind up losing coverage while meeting all the requirements, chief among them need.

What Republican supporters of the bill call a “work requirement,” the Center for American Progress and the ARC call a set of new paperwork requirements that will only save money because they cause people who are eligible — including through their efforts in the waged labor market - to lose their health insurance. Again, aside from some crass remarks about people’s need to work (not really what this is about) and suggestions that people really should get insurance through their jobs, Republicans who voted for the package barely bothered to argue for the wisdom of people losing health care access because of a failure to demonstrate repeatedly that they are working enough hours, or failing repeatedly to prove that one falls into one of the categories of people who are not obliged to work for wages. Nobody said it would be morally improving, or would help one form or sustain a two-parent family, or provide an inspiring model for one’s children.

There is similar bureaucratic disentitlement on deck, as well as a straight-up benefit cut, in the SNAP food assistance program. In the words of a piece by Julia Moskin in The New York Times: The legislation will make it more difficult for people to qualify for benefits, and reduce those benefits for those who are eligible. For example, under the current rules, most people — except parents with dependents — must remain in the work force until age 54 in order to qualify. The bill raises the working age to 64, and exclude only parents with children younger than 7. But remember that what we are really talking about is persistently proving one’s participation in the waged labor market, which is different from participating in it. Also that this requirement is not sensitive to the availability of work, of transportation limitations and needs, and other barriers to waged work.

Image: A yellow sign with a picture of a grocery bag, reading “We Accept SNAP” in a store window. From Futbolete News, https://futbolete.com/us/calfresh-snap-payments-292-sun-bucks-california/

The truly worst thing about the bill, in my view, is its gargantuan increase in funding for ICE, already the knife’s edge of the administration’s anti-Latino, anti-worker, anti-rule of law agenda. An engrossed national police force apparently under the President’s control will certainly not help level the economic plains field. The additional funding will allow for more surveillance, more brutal capturing of people on U.S. soil (some citizens, some green card holders), more incarceration under problematic conditions, and more transportation to dodgy third countries (not the people’s countries of origin). According to the Brennan Center for Justice:

The legislation makes U.S Immigration and Customs and Enforcement the largest federal law enforcement agency, giving it $45 billion for building new detention centers in addition to $14 billion for deportation operations. It also includes $3.5 billion for reimbursements to state and local governments for costs related to immigration-related enforcement and detention.

The bill funds an expansion to approximately double immigrant detention capacity, from about 56,000 detention beds to potentially more than 100,000. Private prison firms — many of which were significant financial supporters of GOP candidates for Congress as well as the president’s election campaign — will reap major financial benefits from this spending, as nearly 90 percent of people in ICE custody are currently held in facilities run by for-profit firms.

Below are reflections on an alternate way of thinking about poverty and anti-poverty policy, from a time when at least a big portion of academic and government attention was trained on the “war” against need amidst plenty and not a “war” against people seeking better economic lives for themselves and their families by moving to the United States, or a “war” against poor people who are unable to meet bureaucratic requirements to prove their worthiness of basic survival.

This is an abridged version of my essay, “Is Work the Only Thing that Pays? The Guaranteed Income and Other Alternative Anti-Poverty Policies in Historical Perspective,” from the Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy 4/1 (Winter, 2009):

I. Introduction

Drawing upon historical examples and the wisdom of advocates as well as researchers, two alternative approaches [to the poverty problem other than the work-or bureaucratic disentitlement-centered one] suggest themselves. The first follows the example of [my former employer] the U.S. House Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families [chaired by Congressman George Miller and under the leadership of Ann Rosewater and Alan Stone], which was itself a response to the changes that occurred in social policy in the early 1980s, and ultimately a casualty of the Republican legislative takeover in the middle 1990s.[9] This approach takes the family, whether straight or gay, single-parent or two-parent, as the unit of political analysis. The family-based agenda treats universal social services as a key solution to the poverty problem. Universal child-care on a French or Swedish model, or health care on a Canadian or British model, would relieve poverty by removing a set of expensive and necessary family expenditures from the market (“de-commodification,” in Gosta Esping-Anderson’s phrase[10]). Such services speak to family needs that stretch across the income spectrum, as well as across other social differences, and so they alleviate poverty without stigmatizing the poor. Although politically difficult to initiate, such proposals are more appealing the more they address the circumstances and values of people who already know that they are compelled to over-identify with their market work.

. . . Drawing upon my research on the welfare rights campaigns of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the other alternative that suggests itself is a strategy based on income rather than on mainstream work. This is, in a sense, the simplest possible approach to poverty, in that it proposes that each adult citizen receive a basic adequate income from a combination of market and state resources; if someone is not earning a wage, then she or he receives substantial support from the government and in the case of a low wage, receives a smaller supplemental grant. Forty years ago, this approach produced a variety of proposals for what was termed the national guaranteed income or negative income tax. In recent years, its most significant embodiment has been the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which has grown in value and coverage substantially since the early 1990s.[12]

. . . An income-based approach to poverty lacks the political appeal of approaches that take the labor market as their starting point. However, as I discovered in my research, it has had many strengths. First, an income-based approach recognizes the reality of long-term and structural unemployment as well as under-employment.

Second, it allows for consideration of the particular vulnerability to poverty of women, especially mothers of young children. Women have been disproportionately poor, and disproportionately the objects of anti-poverty policy, throughout Anglo-American history. The contemporary reasons for women’s disproportionate need for state-funded economic aid include segregated labor markets; part-time work; limited access to private-sector benefits or to public-sector ones that are based on wages or hours; post-divorce or post-separation declines in income; limited child support awards or collections; and domestic violence and the costs of fleeing an abuser. As recent research has demonstrated, the women on late twentieth and early twenty-first century welfare rolls have overwhelmingly been victims of intimate violence.[14] Family homelessness, which arose in the 1980s, has been largely a product of intimate violence, on the one hand, and a tattered system of mental health and income supports, on the other.[15]

Third, an income-based approach de-stigmatizes the poor, at least in theory, in that it rests on the idea that all citizens are vulnerable to periods of low income. This approach promotes as a component of citizenship the right to be free from poverty regardless of its origins. Negative income taxes and similar policies gather together in their recipient pool the very poor and the so-called “working poor,” and suggest a political coalition between these groups. Although not universal in the sense of offering a benefit to people of all social classes, income-based policies are at any rate not categorical in their application (unlike TANF, Supplemental Security Income, and other policies whose lineage begins with the Social Security Act of 1935) and do not therefore demand the separations between groups of people that proved so devastating to both the reputations and the political health of the categorical programs in the decades after the 1930s.

In what follows, I explore the meaning and history of the idea of a minimum income for all U.S. citizens. Although this idea seems far from mainstream policy consideration in the twenty-first century, I argue that it was an object of serious discussion by intellectuals, advocates, and government officials during the Johnson and Nixon years. I explore the reasons for its emergence, and both the strengths and weaknesses of the idea as it came into being. I frame my discussion with reference to the Nixon administration’s Family Assistance Plan (1969-1972), a massive national income support program, which was the most historically significant effort to translate the idea of a guaranteed income into a concrete legislative proposal.

II. A Guaranteed Income: The Idea

In January, 1969, as Richard Nixon assumed the presidency, the idea of a minimum income for all U.S. citizens was so commonplace that one political insider suggested it was one of the two domestic policy proposals that could unite the Republican Party.[16] The idea was nearly as common among leading Democrats, and among policy intellectuals from all points on the political spectrum, as it was among Republicans. From economist Milton Friedman to Senator George McGovern, a remarkable range of political thinkers in the 1960s and early 1970s settled upon the income guarantee as a logical next step in poverty policy, and as an important balance-wheel of what they were beginning to call the “post-industrial” economy.[17] Guaranteed income proposals also lay at the heart of the political program of the grassroots movement for welfare rights, a movement of welfare recipients and their allies that had chapters in every major city of the U.S. These grassroots activists ultimately devoted an enormous amount of energy to defeating Nixon’s Family Assistance Plan proposal, which contained a national guaranteed income as well as work requirements for some recipients of aid. However, they advanced their own proposal for a guaranteed income, the so-called Guaranteed Adequate Income, which was set to a standard of living that exceeded mere subsistence and contained no specific quid pro quo for recipients in the form of employment.[18]

The idea of the guaranteed income was that the national government should insure the citizenry against extreme poverty. Like the categorical aid programs under the Social Security Act, and unlike Old-Age Insurance under Social Security, most guaranteed income plans provided that payments from the Treasury would go to those who could demonstrate a need for them. Unlike the categorical programs, citizens only needed to demonstrate low monetary income to establish need. They did not need to demonstrate in addition that they were disabled from working, or entitled to receive financial help because of the service they did to the nation by raising children. They did not need to prove to caseworkers or local administrators that they were worthy of assistance on account of their behavior. From both the political right and the left, the guaranteed income proposals of the 1960s and early 1970s eliminated caseworkers and the layers of state and local bureaucracy that administered the categorical programs. One version of the guaranteed income, which Friedman advocated as an alternative to all other anti-poverty policies, was a negative income tax that the Internal Revenue Service would administer along with other taxes. Under Friedman’s proposal, citizens or families with incomes below a certain level would not only cease to owe taxes, but would receive money back from the federal treasury.[19]

The idea of a guaranteed income represented a major departure in social welfare thinking since the New Deal. A comprehensive, universal income guarantee would have dulled the edge of many of the classic forms of stratification that existed within the U.S. welfare state, including forms of stratification inherited from public poor relief in the late eighteenth century, from private charity in the nineteenth century, and from the proto-welfare state policies of the Progressive period.[20] It would not, of course, have dulled the edge of distinctions between those who received private health care and other “fringe benefits” and those who received public benefits, or between those who received relatively well-paying public benefits based upon their earnings (such as Unemployment Insurance and Old-Age Insurance) and those who received relatively miserly benefits that were not based upon earnings.[21] However, an income guarantee would have eased the distance between workers at the low end of the income scale (and those, such as laundry workers, farm workers, and many part-time workers, who were not covered by the Old-Age or Unemployment Insurance programs in the middle 1960s) and the categories of people who received public assistance between the 1930s and the 1960s. They would all have been eligible for the same grants or wage supplements. The income guarantee would have diminished the power within the welfare state of the wage-work ethic for men and what social welfare historian Mimi Abramovitz has termed the “family ethic” for women, since men who were outside the labor market and women who had neither children nor male partners would have received the same benefits (scaled for family size) as those in the labor market and/or in nuclear families.[22] An income guarantee for all citizens would also have delimited the position of relative privilege enjoyed by the categorical aid recipients under Social Security, that is, between those who were, in historian Linda Gordon’s phrase, “pitied but not entitled” and those who were not even pitied under the New Deal state system.[23]

Advocates of the negative income tax first formulated the idea in the 1940s.[24] However, the concept of ensuring that all Americans had minimal incomes found a place at the table of national policy only fifteen to twenty years later. Postwar social criticism concerning the relationship between the state and the economy, public poverty policies, and the combination of the civil rights movement, black migration, and urban riots raised aloft a set of problems that the guaranteed income appeared to answer. The relevant social criticism discussed the U.S. as an affluent society with a powerful and ever-growing economy fueled by rapid technological change. The problem the literature raised was unemployment or underemployment, particularly for men of color and white working-class men, which the critics viewed as a consequence of the very forces that led to affluence. Journalistic and academic writing about poverty, and the anti-poverty rhetoric of the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations, raised the problem of persistent poverty in socio-geographic corners of the U.S. that affluence somehow had missed. The social movements, continued migration, and riots all raised the problem of African-American discontent. By the late 1960s, when the Nixon administration and its congressional allies finally translated the idea of a guaranteed income into statutory language, it had come to represent a kind of anti-New Deal and anti-War on Poverty, a response to the problems of male under-employment, persistent poverty, and black rage that differed from anything the U.S. had yet tried.

III. The Guaranteed Income as a Policy for the 1960s [i.e., it was a response to new technology & the twin prospects of vastly greater productivity and a mass lack of access to the fruits of that new productivity, as we see today]

After its initial introduction in the 1940s, the guaranteed income idea resurfaced within the increasingly heated public conversation about poverty in the Kennedy era. It also emerged from the postwar conversation about American affluence. The starting point for the closely related conversations about poverty and affluence was the effect of new technology and new ways of organizing work on the post-World War Two U.S. economy. Worker productivity, national growth, and economic efficiency were seen to have improved almost to dangerous degrees since the war. . . . The critics predicted that productivity gains would lead to such a large decline in the need for labor that social values would change, with the search for meaningful forms of leisure largely replacing a commitment to remunerative work, with unemployment increasingly accepted as a normal byproduct of the economic structure, and with consumption eventually replacing production as the society’s paradigmatic economic activity and as the rock on which Americans formed their identities.

The economic and social changes that the critics predicted were particularly alarming because they signaled potential emasculation or feminization. Masculinity would certainly have to change, if not diminish, it appeared, as the social need for men’s work, the physical intensity of their work, and their autonomy in performing it all declined.[26] The danger of feminization united men across the class spectrum and racial divide in 1950s and 1960s social criticism, applying equally to David Riesman’s “other-directed” men of the modern corporation,[27] Paul Goodman’s unfree middle-class students,[28] and the redundant working-class black men whom Daniel Patrick Moynihan believed needed to “strut” to avoid obliteration at the hands of both large-scale economic forces and the matriarchal women in their lives.[29] All of these men were potentially vulnerable to the shift in social emphasis from the activities that had been coded as masculine in Europe and the U.S. since at least the early nineteenth century to those that had been coded as feminine.[30]

The other side of the coin of considering the possibly deleterious effects of American affluence was an increasing concern in the late 1950s and early 1960s about the persistence of poverty amid prosperity. John Kenneth Galbraith showed both faces of the coin in The Affluent Society.[31] The Affluent Society decried a social over-emphasis on production or industrial output that continued although such output spoke to no obvious or natural needs. Galbraith claimed that much of the production that occurred in the private market was more significant for keeping people working, and therefore earning (and spending what they earned), than for meeting human needs. By way of remedy, he urged “social balance” in the form of investments in public goods, such as schools, hospitals, and roads, which approached the levels of private investment that drove the postwar economy. To finance such investments, he urged higher taxes, especially sales taxes, which had the twin virtues of raising revenue and discouraging consumption.[32]

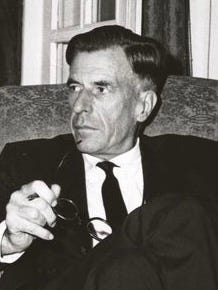

Image: Photo of a white man in a dark suit with dark tie and glasses in hand: Economist John Kenneth Galbraith, from the time when he was Ambassador to India under President Kennedy, 1962. Photo uncredited, courtesy of Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Kenneth_Galbraith

The poverty Galbraith observed was of two types, “case” and “insular.” Case poverty had to do with personal disabilities or shortcomings, whether physical or psychological, that prevented people from taking advantage of opportunities. Insular poverty, on the other hand, transcended the individual. It was the outcome of uneven development and technological change, combined with a “homing instinct” that made people desire “to spend their lives at or near the place of their birth” instead of moving someplace more economically productive.[33]

Since he believed that poverty, especially of the “insular” type, was inescapable under modern conditions, Galbraith urged state action to ameliorate it. He argued that it was increasingly important to make employment available to everyone who sought it, since the “discrimination” between those with jobs and therefore income, and those without, was “altogether too flagrant.”[34] As a further hedge against such discrimination, Galbraith sought “a reasonably satisfactory substitute for production as a source of income. This and this alone,” he argued, “would break the present nexus between production and income” and allow the U.S. to move away from excessive private output without generating mass unemployment and misery.[35] The key “substitute” that Galbraith proposed was unemployment compensation, which he believed should be more widely available than it was in 1958 and available for longer periods of time; in later editions of The Affluent Society, he openly advocated a guaranteed income.[36] To objections he anticipated to the idea of providing income to citizens without demanding that they earn it by producing something, Galbraith asked:

[I]f the goods have ceased to be urgent, where is the fraud [in not working to produce more and more goods]? Can the North Dakota farmer be indicted for failure to labor hard and long to produce the wheat that his government wishes passionately it did not have to buy? Are we desperately dependent on the diligence of the worker who applies maroon and pink enamel to the functionless bulge of a modern motorcar? The idle man may still be an enemy of himself. But it is hard to say that the loss of his effort is damaging to society.[37]

Galbraith asked his readers to consider a “divorce of production from security,” untying the knot between a worker’s marketable output and his or her income.[38]

As the 1950s became the 1960s, Michael Harrington’s The Other America succeeded Galbraith’s Affluent Society as the touchstone text on poverty in the United States. The difference between The Affluent Society and The Other America was one of emphasis more than of argument. Where Galbraith devoted most of his book to the problems that affluence posed, and spent one chapter on the problem of poverty, Harrington devoted his entire work to naming poverty as a social problem. Harrington, like Galbraith, wrote of the contrast between large-scale prosperity and persistent poverty, and argued that the two were not merely coincidentally but also causally related to one another. “The other Americans,” according to Harrington, “[were] the victims of the very inventions and machines that have provided a higher living standard for the rest of the society. They are upside-down in the economy, and for them greater productivity often means worse jobs; agricultural advance becomes hunger.”[39]

Galbraith and Harrington both understood postwar American poverty as a minority phenomenon, but not one that could therefore be ignored or expected to wash away in the general tide of economic growth. However, Harrington objected to Galbraith’s idea of “island” poverty because, he claimed, it implied “a serious, but relatively minor, problem.”[40] In place of Galbraith’s typology, Harrington employed the idea of the “culture of poverty” to argue that some people would not respond in simple or predictable ways to economic change. Harrington’s “culture of poverty” at first emerged from structural and environmental factors, but later in life (or in a second generation) was self-perpetuating.[41] The culture was “an institution, a way of life,”[42] “a fatal, futile universe,”[43] “an underdeveloped nation . . . beyond history, beyond progress, sunk in a paralyzing, maiming routine.”[44] He offered no specific governmental plan for the “other America.” However, Harrington argued that the self- perpetuating poverty culture resisted normal economic incentives and required a targeted national response.

In January, 1963, Dwight Macdonald underlined and expanded upon the arguments of The Other America in an influential essay for The New Yorker on Harrington and poverty.[45] The Macdonald review exerted a greater direct impact on public policy than Harrington’s own work, since it appears to have been Macdonald, and not Harrington, whom John F. Kennedy read before formulating his anti-poverty proposals.[46] Macdonald also connected Harrington’s and Galbraith’s ideas about poverty and economic structure to the idea of a guaranteed minimum standard of living for all U.S. citizens. Macdonald joined the critical consensus when he warned about the potential social impact of industrial automation.[47] He joined Harrington in reflecting upon what he saw as the special character of the “new minority mass poverty” of the age of affluence, a poverty “isolated and hopeless” and probably “chronic.”[48]

In his New Yorker piece, Macdonald treated the essence of the poverty problem as a problem of consumption. For Macdonald, participation in the consumer economy was not the wasteful error it was for Galbraith; rather, it was the key sign of social membership or inclusion in the United States of 1963. Macdonald defined poverty in terms of model family budgets that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (B.L.S.) drafted to describe “‘adequate living.’” He commented on these budgets:

This is an ideal picture, drawn up by social workers, of how a poor family should spend its money. But . . . only a statistician could expect an actual live woman, however poor, to buy new clothes at intervals of five or ten years. Also, one suspects that a lot more movies are seen and ice-cream cones and bottles of beer are consumed than in the Spartan ideal. These necessary luxuries are had only at the cost of displacing other items—necessary, so to speak—in the B.L.S. budget.[49]

The “necessary luxuries” that poor people would need to do without, or for which they would have to sacrifice other necessities, largely defined participation in postwar social life for Macdonald. While he accepted the claim that general economic prosperity and ameliorative welfare payments together had eliminated starvation in the U.S., Macdonald insisted this was unacceptable as long as “a fourth of us are excluded from the common social existence. Not to be able to afford a movie or a glass of beer is a kind of starvation,” he added “-- if everybody else can.”[50]

Consumer deprivation, combined with the sense he shared with Galbraith and Harrington that “a hard core of the specially disadvantaged”[51] were relatively immune to general economic expansion, also formed Macdonald’s justification for state action against poverty. “To do something about this hard core,” Macdonald argued:

a second line of government policy [other than macroeconomic] would be required; namely, direct intervention to help the poor. We have had this since the New Deal, but it has always been grudging and miserly, and we have never accepted the principle that every citizen should be provided, at state expense, with a reasonable minimum standard of living regardless of other considerations. It should not depend on earnings, as does Social Security. . . Nor should it exclude millions of our poorest citizens because they lack the political pressure to force their way into the Welfare State. The governmental obligation to provide, out of taxes, such a minimum living standard for all who need it should be taken as much for granted as free public schools have always been in our history. [52]

The article ended with a hope for the day when “our poor can be proud to say ‘Civis Americanus sum! [I am an American citizen].’” Macdonald wrote: “[U]ntil the act of justice that would make this possible has been performed by the three-quarters of Americans who are not poor -- until then the shame of the Other America will continue.”[53]

IV. Fear of a Poor Black Nation? Civil Rights and the Income Ideal

The black civil rights movement influenced demands for a guaranteed income as much as did the writing about poverty and economic structure in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Harrington’s and Macdonald’s visions of poverty as in part intractable relied upon their common understanding that a meaningful fraction of the poor was African American, excluded from the new prosperity by racial discrimination and by a lack of the educational background they believed workers needed to fit into the changing labor market.[54] The civil rights movement, South and North, placed concerns about African American economic advancement on the national agenda. Although the elision between poverty and racial difference was an old one in the U.S., movement demands for equal justice at the work place and the lunch counter, as well as at the polling place and the court house, compelled many whites to see how little the affluent society had offered black communities.[55]

The civil rights movement’s Birmingham campaign and the March on Washington, both of which occurred in 1963, enhanced the movement’s appearance of efficacy and its leaders’ self-confidence. These two events also brought into focus the connections between formal civil equality between blacks and whites and their relative economic circumstances. In Birmingham, the multi-part agreement between the city’s merchants and civil rights activists encompassed desegregating fitting rooms, wash rooms, and lunch counters, hiring more black sales people and cashiers, and making a commitment to improve African Americans’ employment options in the future.[56] The March on Washington united support for the freedoms at issue in the Civil Rights Bill then before Congress with calls for full employment and an end to racial discrimination in hiring.[57] In his “I Have A Dream” speech at the March on Washington, Martin Luther King, Jr., called for economic justice as well as for the formal equality that would allow whites to judge his children not “by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”[58] King drew upon the imagery that Galbraith popularized, of “island” poverty. “One hundred years” after the Emancipation Proclamation, King said:

the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity . . . In a sense we have come to our nation’s Capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. . . .

Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check; a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’ But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check -- a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.[59]

King followed this language with more sanguine, and familiar, calls for nonviolent protest and an end to segregation in the South. But his gentler political rhetoric did not negate his insistence that African Americans receive a raft off the island of poverty “upon demand,” or his judgment that the “promissory note” from prosperous white to impoverished black America was long past due.

The guaranteed income idea was only one of many possible responses to demands such as King’s. In some ways, it was a politically expedient answer that accommodated beliefs about black inferiority and ultimate inability to succeed in a predominantly white labor market. Given the assumption of affluence -- including the idea that the U.S. economy had defeated the business cycle and that economic growth could continue indefinitely -- direct income grants to a multitude of people who were outside the labor market, while costly in dollar terms, may have seemed a relatively small price to pay for social peace. Guaranteed income schemes were politically expedient in that they allowed bureaucrats, legislators, and intellectuals to avoid other, more politically complicated, options, such as making a full-out effort to desegregate trade unions and private-sector work forces. The guaranteed income was also an alternative to the full employment policy that activists had sought at the March on Washington, and to the turn toward increased taxation and increased investment in public goods that Galbraith had advocated in The Affluent Society. However, despite their limitations, guaranteed income proposals represented a response to the claims of civil rights activists that African-Americans deserved equal treatment both economically and politically – and that “equality of opportunity,” the great catch-phrase of the Kennedy years, was not sufficient to ensure economic equality.

V. Men and Markets

One major conservative contribution to the public conversation about guaranteeing incomes was Capitalism and Freedom, by Milton Friedman and Rose Friedman, which appeared in 1962. Capitalism and Freedom was a quintessential text of the Cold War era, an extended argument for capitalism as a system of “economic freedom and a necessary condition for political freedom.”[60] The work launched the idea of a negative income tax, or guaranteed income administered by the IRS, into Republican policy parlance.

While they were hardly Keynesians, the Friedmans nonetheless treated as obvious the conclusion of such Keynesians as John Kenneth Galbraith that poverty was a serious and remediable social problem, and that the national government had a legitimate role to play in alleviating it. . . . [T]he Friedmans argued for a national system of cash transfers to replace all forms of state social welfare provision. The instrument for enacting these transfers was to be the income tax system.

. . . In 1962, Milton and Rose Friedman justified the negative income tax exclusively as an anti-poverty measure. They argued that such a system was superior to conventional public welfare measures because it answered the problem of poverty most directly. Moreover, a negative income tax made “explicit the cost borne by society” for social welfare—as opposed to the patchwork of social policies that obscured their total costs. The proposal was attractive to the Friedmans because it was “outside the market,” unlike, for example, minimum wages, which structured employer choices, or a national health care system, which would compete with and in part supplant privately provided goods. Finally, they favored negative income taxes because, although they might reduce the work ethic somewhat by softening the sting of an individual’s choice not to work, they also allowed for work incentives. “An extra dollar earned,” they wrote, would “always mean[ ] more money available for expenditure.”[64] . . . . .

VI. The War on Poverty, The War in Vietnam, and the Guaranteed Income Idea

The guaranteed income idea rose to the fore in policy circles at the same time as did a range of other ideas for alleviating poverty. John F. Kennedy had committed himself to doing something about poverty during his pivotal West Virginia primary campaign in 1960.[66] However, the Kennedy administration did not advance a particularly ambitious anti-poverty program, in part because of its thin electoral mandate and the opposition it faced in Congress from Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats.[67] Consistent with Galbraith’s idea of “island” poverty, the Kennedy administration focused upon an agency called the Area Redevelopment Agency, which made federal grants to regions that were seen to have been left behind by the new economy.[68] Kennedy administration officials also funded anti-poverty programs through the President’s Committee on (and later the federal Office on) Juvenile Delinquency, which proceeded on the theory that social factors, especially poverty, inspired juvenile crime and misbehavior.[69]

After Kennedy’s assassination, the Johnson administration pursued a major tax cut, the Civil Rights Act, and a legislative and administrative war on poverty.[70] The guaranteed income idea does not appear to have figured much in the thinking of Johnson or his wise men when they planned the War on Poverty, or drafted its central legislation, the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964.[71] However, the guaranteed income idea survived the Johnson presidency. The key bureaucracy of the War on Poverty, the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), contained a column of guaranteed income advocates. While most of the agency’s institutional resources went to managing the Community Action Program and other programs, OEO also contained a cadre of policy experts who repeatedly drafted plans for a negative income tax. In the first year of OEO’s existence, for example, they drafted a five-year plan, which they did not release to the public or to Congress, which included a provision for a negative income tax of $1,738 per year for a family of four with no other income.[72] OEO staff incorporated some version of a negative income tax into plans they drafted in 1966, 1967, and 1968.[73]

Even without Johnson’s backing, the negative income tax appealed to a group of policy professionals in Washington, D.C. It was at once grand enough in scale to appear to meet the “welfare crisis” and sufficiently different from both New Deal and Great Society social policy that it appeared as a departure. As a potential answer to the labor-market position of African American men, the stock of the guaranteed income idea rose as riots and Northern protests illuminated the unemployment of black men in the cities, the gap between their unemployment rates and those of whites, and their fury.[74] The draft and the War in Vietnam made the work situation for men of color temporarily less stark than it would otherwise have been. But returning veterans without jobs were grim reminders of the weakness of war as an employment policy.[75]

Proposals for the guaranteed income and negative income tax enjoyed a renaissance later in the 1960s. A front-page Wall Street Journal article in 1966 reported the interest of Johnson Administration officials in the guaranteed income concept -- as well as the support of John Kenneth Galbraith and New York’s liberal Republican mayor, John Lindsay, for it. However, the article also reported: “Vietnam-induced budget strains and Johnsonian political caution” prevented the Administration from doing more than tinkering with existing welfare programs.[76] It took a few more years of urban riots—from the Harlem conflagration in 1964 through the national response to King’s assassination in April, 1968—and continued protests by the Northern civil rights movement to persuade many whites that the War on Poverty was not following a sufficiently ambitious battle plan. “In retrospect,” Moynihan wrote, “the negative income tax appears very much an idea whose time to come was the late 1960s.”[77]

In January, 1967, Johnson responded to pressures internal and external to his Administration and announced his intention to appoint a national commission on income maintenance programs. The Commission’s central mission was to report on the strengths and weaknesses of the guaranteed income and negative income tax ideas. At the same time, OEO researchers began a study of the effects of the negative income tax upon one thousand families in New Jersey.[78] Johnson ultimately appointed the income-maintenance commission, headed by railroad industrialist Ben Heineman, in 1968. Nearly a year into the Nixon administration, the Heineman Commission reported its findings, and its strong support for a negative income tax, in a report titled Poverty Amid Plenty: The American Paradox.

VII. A Republican War on Poverty?

While the Johnson Administration dawdled in its approach to guaranteeing incomes, East-Coast Republicans came increasingly to favor the idea. The “welfare crisis” in New York made Governor Nelson Rockefeller a ready audience for such a proposal. He joined Mayor Lindsay, a fellow liberal Republican with similar ambitions for national office, in answering the rising welfare rolls and continuing activist pressure with a call for the federal government to re-make the welfare system.[79]

Rockefeller first responded to the “welfare crisis” by taking measures at the state level that were consistent with federal law: In 1968, he proposed a “flat grant” for all public assistance recipients that was slightly higher than the basic grants they had previously received. The “flat grant” proposal would have saved New York State money, and would have made welfare administration more manageable, because it allowed little discretionary spending authority to local welfare officials or individual case workers. Previously, these low-level officials had the power to calculate family welfare budgets (within given parameters but also according to their assessments of family needs) and to disburse potentially large additional grants for families’ occasional needs.[80] The “flat grant” was not a minimum income because it did not apply to all citizens. However, it was a definite stride toward a minimum income, away from the budget-based, highly discretionary welfare system of the period between 1935 and the late 1960s.

The fate of Rockefeller’s “flat grant” proposal presaged the fate of the Family Assistance Plan under President Nixon. Rockefeller’s plan failed in the New York State legislature in 1968. Welfare activists opposed it because they saw it as in effect a grant cut and as a blow to their opportunities for organizing against local targets that had discretionary spending authority. Upstate legislators also opposed the plan, which they saw as a generous guaranteed income for New York City welfare clients.[81] A less generous proposal passed in 1969.[82] While the proposals were being debated, and even after New York changed its welfare law, protests continued.[83]

Rockefeller, Mayor Lindsay, and Lindsay’s welfare chief Mitchell Ginsberg viewed the administration of public assistance programs as unmanageable. They argued that the costs could no longer be borne by the cities or states alone.[84] They all ultimately called upon the federal government for relief, seeking to nationalize programs that had been radically decentralized since their inception in the New Deal. At hearings on the Nixon welfare proposals before the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, Lindsay argued that the “single most far-reaching reform would be complete Federal financing and administration of the welfare system. . . It would be unthinkable not to have Federal financing and administration of the social security system. . . From the perspective of a few years, it would seem unthinkable to do it any other way.”[85]

To clarify his options, both as Governor of New York and as a potential candidate for the Republican nomination for President, Rockefeller organized a small conference on welfare options in March, 1967. Moynihan remembered this conference as a “formative event” in the coalescence of Republican sympathy for the guaranteed income idea. The meeting debated the merits of a negative income tax versus those of a European-style family allowance, with Milton Friedman speaking for the former and Moynihan for the latter. A steering committee of participants at the meeting, headed by the Chief Executive Officer of the Xerox Corporation, and composed primarily of other corporate executives, approved both ideas but expressed a preference for the negative income. After Rockefeller’s conference, this steering committee continued to press for replacing the welfare system with either a family allowance or negative income tax, and brought its recommendations before a business-oriented lobbying group, the Committee for Economic Development, in May, 1968.[86] Although Rockefeller did not promise a negative income tax in his effort to win the Presidential nomination, in the 1968 electoral season, the liberal Republican Ripon Society favored the idea, and the leader of the House Republican Conference, Melvin Laird, edited a book that included Milton Friedman’s brief for a guaranteed income.[87]

By the time of the 1968 Presidential election, the idea of a guaranteed income had traveled a remarkable distance from its origins in the margins of John Kenneth Galbraith’s vision of an affluent postwar society or the efforts of Milton and Rose Friedman to find a philosophically palatable alternative to New Deal-style positive state programming. In the spring and summer of 1968, Great Society and New Deal solutions to the problem of maintaining social peace lay in shambles. Political and economic elites, no less than mobilized groups of African American activists or disillusioned college students, had ceased to believe that either public assistance or community action could right the balance. For all of the reasons that explained its longevity throughout the 1960s—not least its elasticity as a concept and its openness to multiple interpretations— the guaranteed income idea was poised to enter the domestic agenda of the incoming President, virtually without respect to Party.

VIII. Conclusion

What does the intellectual and political campaign for a guaranteed income in the United States have to offer [people] concerned with poverty at the beginning of the twenty-first century? First, and most importantly, the history of the demand for a minimum national income serves as a reminder that [a wage-work-centered approach, which often devolves into mere bureaucratic disentitlement] is not the only possible approach to anti-poverty policy. Indeed, as the economy falters . . . the economic analyses of John Kenneth Galbraith, Michael Harrington, and others may be more relevant than they have been for many years. . . . [M]any would recognize in contemporary circumstances echoes of Galbraith’s, Harrington’s, and McDonald’s concerns about the effects of technology on the structure and size of the labor market. The “discrimination,” in Galbraith’s language, between those with jobs and those without has become extremely stark, as has the gulf between those with full-time, primary-sector jobs with benefits and those who work outside this shrinking, privileged tier.

One of the most instructive elements of the history of the guaranteed income in the postwar United States is the breadth of support that existed for it. While many Democrats were intrigued with the idea, leading Democratic politicians, such as President Johnson, were skeptical. But Republicans such as Nelson Rockefeller and conservative intellectuals who opposed the welfare state, such as Milton and Rose Friedman, were engaged with the idea. To some degree, advocates for poor people in the U.S. since the 1970s have already learned that conservatives and libertarians may support income transfers if they are conducted with minimal government bureaucracy. . . .

For women and their families, the history of the proposal for a national minimum income offers both hope and a warning. The hope lies in the fact that guaranteed income proposals were by design universal (or, if limited, limited to all families raising children), in the sense that their only eligibility criteria were financial ones. If implemented today, such a program would liberate impoverished women from the intrusive and moralistic procedures they still must endure when they become clients of the U.S. welfare state. Moreover, a universal citizenship income would make women raising children without sufficient economic resources far less vulnerable politically than they have been for most of U.S. history. By including low-income mothers in a general program for poor people, a guaranteed income policy would make them part of a large group with some political clout, and would eliminate the special categorical program that has served women and children since the 1930s (today called Temporary Assistance to Needy Families), with its tenuous hold on national political sympathies. The warning lies in the way guaranteed income proposals that were generated as a response to historically high rates of unemployment and under-employment might be used to justify the exclusion of women from the first-tier labor market or from training programs for non-traditional jobs. . . .

Similarly, for African Americans, the history of the idea of a guaranteed income contains both promise and risk. Proposals for a national minimum income in the 1960s were provoked by the demands of the civil rights movement and by policy makers’ fears of urban riots. However, many African American activists demanded jobs rather than government income supports, and others demanded jobs or income. Policy intellectuals who offered income alone as a solution to African American unemployment and poverty appear to have wanted an answer to civil rights demands that would be less controversial among working-class white voters than special training programs and aggressive enforcement of anti-discrimination mandates would have been. Today, given that African American citizens still face egregiously high rates of unemployment and under-employment, a national income policy would certainly help to ease the economic disparities between whites and blacks. As in the case of mothers and children, a universalistic, income-based program would also soften the political vulnerability of social programs that disproportionately target citizens of color. The risk in creating such a program is that its existence would help naturalize unemployment for African Americans, and would become an argument against making investments in public schools, adult education, training programs, affirmative action programs, or civil rights enforcement.

Overall, the most successful solution to the problem of poverty in the early twenty-first century is likely to be a combination of [improving work and the returns to work, themselves,] a family-based strategy, and a functioning support system of basic income for those who earn very little or nothing. This hybrid approach to the poverty problem is both philosophically and practically preferable to a one-dimensional approach. Many people in the United States are simultaneously workers, parents, and consumers. Government has potential roles to play in structuring the labor market and counteracting its weaknesses, ensuring that families get the services they need, and helping people acquire what they need in the consumer marketplace. None of these approaches has a monopoly on moral, philosophical, or practical political legitimacy. Together, these multiple approaches might point the United States toward a future not merely of ending welfare but finally of moving beyond it.

* I acknowledge the contributions to my thinking of Peter Edelman, Liz Schott, Julie Nice, and all of the other participants in the Symposium, “Ten Years After Welfare Reform: Making Work Pay” at the Northwestern University School of Law. I also acknowledges the assistance of Hendrik Hartog, Daniel Rodgers, Elizabeth Lunbeck, Lizabeth Cohen, Daniel Horowitz, Anore Horton, and many others in helping me think through these ideas.

[1] For the thinking that underlay Clinton’s decision to make welfare a target during the 1992 presidential elections, and that encouraged him to sign the welfare reform bill initiated by congressional Republicans in 1996, see Stanley Greenberg, Middle Class Dreams: The Politics and Power of the New American Majority 110-11 (1995). Greenberg was the leading pollster for candidate Bill Clinton in 1992, and a political advisor thereafter. On the legislation itself, see Joel F. Handler and Yeheskel Hasenfeld, Blame Welfare, Ignore Poverty and Inequality 282-83 (2007).

[2] Bob Schelhas (ed.), The Contract with America: The Bold Plan by Rep. Newt Gingrich, Rep. Dick Armey and the House Republicans to Change the Nation (1994); Republican National Committee, Contract with America (1994).

[3] Benjamin Wallace-Wells, A Case of the Blues New York Times Magazine (March 30, 2008), http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/30/magazine/30Republicans-t.html accessed on September 3, 2008; George Packer, The Fall of Conservatism: Have the Republicans Run Out of Ideas? The New Yorker (May 26, 2008), http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/5/26/080526fa_fact_packer(last visited Sept. 3, 2008); Eyal Press, Is The Party Over? The Nation (June 2, 2008), http://www.thenation.com/doc/20080602/press (last visited Sept. 3, 2008).

[4] “John Edwards’ Plan to Build One America,” http://johnedwards.com/issues/ (last visited Sept. 2, 2008): “In today’s Two America’s, it is no coincidence that most families are working harder for stagnating wages.” For the origins of the “two nations” image regarding poverty and wealth, see Benjamin Disraeli, Sibyll, or The Two Nations, excerpted in The Portable Victorian Reader 22-23 (Gordon S. Haight ed., 1972); Gertrude Himmelfarb, The Idea of Poverty: England in the Early Industrial Age 489-503 (1983). For the image in regard to race in the United States, see Andrew Hacker, Two Nations: Black and White, Separate, Hostile, Unequal (2003, orig. 1993).

[5] See Presidential Forum on Faith, Values, and Poverty, hosted by Sojourners: Christians for Justice and Peace (June 4, 2008), description and video at http://www.sojo.net/index.cfm?action=action.display&item=pentecost07_candidates_forum (last visited Sept. 3, 2008).

[6] John Edwards, “A National Goal: End Poverty within 30 Years,” http://www.johnedwards.com/issues/poverty (last visited Sept. 2, 2008): “In his vision of a ‘Working Society,’ everyone who is able to work will be expected to work and rewarded for working.” Specific proposals included raising the minimum wage, tripling the EITC for childless adults, and reforming labor law to allow for union representation as the result of card checks rather than traditional, secret-ballot elections.

[7] For a review of scholarship that addresses the place of women and families in U.S. social policy, see Felicia Kornbluh, Women’s History with the Politics Left In: Feminist Studies of the Welfare State, in Exploring Women’s Studies: Looking Forward, Looking Back 236-55 (Carol Berkin, et al., eds., 2006).

[8] For alternative frameworks for social policy, which might be consistent with a guaranteed income approach, see Martha Fineman, The Vulnerable Subject, 20 Yale J. L. and Feminism 1 (2008) (arguing for policies that recognize the universality of vulnerability in human life, and that distribute benefits on the basis of their ability to address vulnerabilities rather than on the basis of their ability to reward market work); Martha Nussbaum, frontiers of justice: Disability, nationality, species membership (2006) (arguing for a “capabilities” approach that respects differences in physical and intellectual ability). I have explored the links between a gendered and a disability-sensitive critique of U.S. social policy in Felicia Kornbluh, Jacobus TenBroek’s Fourteenth Amendment: Civil Rights, Disability, and Law In the Work of America’s Leading Blind Activist Before the 1960s, Society for Disability Studies Conference, Bethesda, Maryland (2006) and Virtually Normal: Jacobus tenBroek, Blindness and Masculinity in Early Disability Rights Discourse, Feminism and Legal Theory Workshop, Atlanta, Georgia (2004), unpublished papers in possession of the author.

[9] Staff of House Select Comm. on Children, Youth, and Families, 98th Cong., Children, Youth, and Families: 1983 (Comm. Print 1983); Staff of House Select Comm. on Children, Youth, and Families, 99th Cong., Children and Families in Poverty: Beyond the Statistics (Comm. Print 1985); Staff of House Select Comm. on Children, Youth, and Families, 100th Cong., American Families in Tomorrow’s Economy (Comm. Print 1987); Staff of House Select Comm. on Children, Youth, and Families, 100th Cong., A Domestic Priority: Overcoming Family Poverty in America (Comm. Print 1988).

[10] Gosta Esping-Andersen, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (1990).

[11] Theda Skocpol, Targeting within Universalism, in The Urban Underclass 411-36 (Christopher Jencks and Paul E. Peterson, eds., 1991). For an alternate view, see Robert Greenstein, Universal and Targeted Approaches to Relieving Poverty: An Alternative View, Id., at 437-59. On health care, see Jill Quadagno, One Nation, Uninsured: Why The United States Has No National Health Insurance (2005).

[12] On the history of the EITC, see Brian Steensland, The Failed Welfare Revolution: America’s Struggle Over Guaranteed Income Policy 178-80 (2008). For general discussion of the EITC, see http://www.cpbb.org/pubs/eitc.htm (last visited Sept. 1, 2008). The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities notes the rise in state, as well as federal, EITC’s. As of June, 2008, twenty-four states had EITC’s, and twenty-one had refundable EITC’s, meaning that people who qualified were not only exempt from state taxes but also received income supplements from the state. Seehttp://www.cbpp.org/6-6/08sfp.htm (last visited Sept. 1, 2008). Moreover, Democrats in the U.S. House and Senate, and local leaders, such as Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York City, have endorsed expanding the EITC for childless workers. As of October, 2007, childless workers were eligible for Earned Income Tax Credits, but the value of these was very low, a maximum of $438 per year, or less than one-tenth of the maximum EITC for a family with one child. See Aviva Aron-Dine and Arloc Sherman, “Ways and Means Committee Chairman Charles Rangel’s Proposed Expansion of the EITC for Childless Workers: An Important Step to Make Work Pay,” http://www.cbpp.org/10/25/07tax.htm (last visited Sept. 1, 2008).

[13] I discuss these alternatives in Felicia Kornbluh, The Battle for Welfare Rights: Politics and Poverty in Modern America 8-9 (2007). See also Bruce Ackerman and Anne Alstott, The Stakeholder Society (1999).

[14] Richard Tolman and Jody Raphael, A Review of Research on Welfare and Domestic Violence 56 J. Social Issues 655- 82 (2000); Jody Raphael, Saving Bernice: Battered Women, Welfare and Poverty (2000).

[15] See the work of Ellen Bassuk, Director, National Center on Family Homelessness, Newton Centre, MA, especially from the Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence Study (1998-2003), described at http://www.familyhomelessness.org/work_past_women.php (last visited Sept. 2, 2008).

[16] On the idea of a guaranteed income, and the Nixon plan as a manifestation of this idea, see Felicia Kornbluh, A Right to Welfare? Poor Women, Professionals, and Poverty Programs, 1935-1975 (2000) (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University); Steensland, supra note 12. On the guaranteed income within the Republican Party, see Daniel Patrick Moynihan, The Politics of a Guaranteed Income: The Nixon Administration and the Family Assistance Plan 63 (1973); Vincent J. Burke and Vee Burke, Nixon’s Good Deed: Welfare Reform 50, footnote (1974). The insider was John Price, a founder of the young Republicans’ group the Ripon Forum and, later, counsel to Daniel Patrick Moynihan at the Nixon administration’s Urban Affairs Council.

[17] For Friedman’s views, see Milton Friedman, with Rose Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (1962). Friedman has remembered his support for the guaranteed income, and his growing disenchantment with the Nixon welfare reform proposal between 1969 and 1971, in Milton Friedman and Rose D. Friedman, Two Lucky People: Memoirs 381-82 (1998). To understand McGovern’s minimum income, or “demo-grant” proposal, I rely upon an interview with Alan Stone, New York, New York, February 11, 1997. Burke and Burke, supra note 16, at 142, point out that McGovern retreated from his universal income proposal in August, 1972, eleven weeks before the Presidential election.

[18] Kornbluh, supra note 13, at 137-60. For more on the Nixon welfare proposal, see Felicia Kornbluh, Who Shot F.A.P.? The Nixon Welfare Plan and the Transformation of American Politics, 2 The 1960s: A Journal of History, Politics, and Culture, forthcoming (Winter, 2008-09); Steensland, supra note 12, at 79-156; and Jill Quadagno, The Color of Welfare: How Racism Undermined the War on Poverty 117-34 (1994).

[19] See discussion below.

[20] On welfare states as systems of stratification, see Esping-Andersen, supra note 10, 3-4: “Social stratification is part and parcel of welfare states. Social policy is supposed to address problems of stratification, but it also produces it . . . The really neglected issue is the welfare state as a stratification system in its own right.” For a single volume on welfare practices from the late eighteenth century through the twentieth century, seeMichael B. Katz, In The Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America (1986).

[21] On private benefits as part of the welfare state, see Esping-Andersen, supra note 10 and Susan Pedersen, Family, Dependence, and the Origins of the Welfare State: Britain and France, 1914-1945 224-88 (1993). On the rise of “fringe benefits,” see Beth Stevens, Blurring the Boundaries: How the Federal Government Has Influenced Welfare Benefits in the Private Sector, in The Politics of Social Policy in the United States 123-48 (Theda Skocpol, Margaret Weir, and Ann Shola Orloff eds., 1988). On the “two-tier” welfare state generally, considered particularly in terms of gender, see Barbara J. Nelson, The Origins of the Two-Channel Welfare State: Workmen’s Compensation and Mothers’ Aid, in Women, The State, and Welfare 123-51 (Linda Gordon ed., 1990); Linda Gordon, Pitied But Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare in the United States 293-95 (1995).

[22] On relationships between U.S. public welfare benefits and the labor market, see Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Regulating the Poor: The Functions of Public Welfare (1971); Katz, supra note 20. On the “family ethic” or relative privilege of mothers over non-mothers, seeMimi Abramovitz, Regulating the Lives of Women (1988). For a comparative view, see Carole Pateman The Patriarchal Welfare State, inDemocracy and the Welfare State 231-60 (Amy Gutmann ed., 1988). For complications of both the work-ethic and family-ethic models, seeFelicia Kornbluh, The New Literature on Gender and the Welfare State: The U.S. Case, 22/1 Feminist Studies (1996) 171.

[23] Gordon, supra note 21.

[24] These were Milton Friedman and his fellow economist, George Stigler. See Stigler, The Economics Of Minimum Wage Legislation, American Economic Review 36 (June, 1946) 358, proposing a negative income tax as an alternative to a minimum wage.

[25] Michael Harrington, The Other America: Poverty in the United States 1 (1981, orig. 1962).

[26] For general discussion of masculinity and post-World War Two social thought, see Barbara Ehrenreich, The Hearts of Men: American Dreams and the Flight From Commitment (1983).

[27] David Riesman, with Nathan Glazer and Reuel Denney, The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character (1989, orig. 1950). As Ehrenreich argues, throughout the work, Riesman referred to the “other-directed person” and not to men per se. However, the change in social character that Riesman described, from autonomy, inner-direction, and material well-being achieved through physically demanding work, was only meaningful in reference to stereotypes of men’s activity and attitudes. “[A] book on ‘other-directed women’ would have been as unsurprising as a book on, say, fair-skinned Anglo-Saxons, because other-directedness was built into the female social role as wives as mothers. The traits that Riesman found in the other-directed personality . . . were precisely those that the patriarch of mid-century sociology, Talcott Parsons, had just assigned to the female sex.” Hearts of Men, 33-34. For similar concerns, see C. Wright Mills, White Collar: The American Middle Classes (1956, orig. 1951).

[28] Paul Goodman, Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized System (1960) and Compulsory Mis-Education (1964). This is not to say that Goodman had an easy relationship with normative masculinity. See his Memoirs of an Ancient Activist, in The Gay Liberation Book: Writing and Photographs on Gay (Men’s) Liberation 22-29 (Len Richmond and Gary Noguera eds., 1973). Thanks to Bruce Aaron for the reference.

[29] Daniel Patrick Moynihan, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, in The Moynihan Report and the Politics of Controversy 39-125 (Lee Rainwater and William Yancey eds., 1967).

[30] See discussion in Victoria deGrazia, Introduction, in The Sex of Things 1-10 (Victoria deGrazia with Ellen Furlough eds., 1997).

[31] John Kenneth Galbraith, The Affluent Society (1958).

[32] Id. at 315.

[33] Id. at 326-27. In later editions, Galbraith specified his idea of island poverty further, to refer to “rural and urban slums” in the South, the urban North, Appalachia, or Puerto Rico. “Race,” he argued, “which acts to locate people by their color rather than by the proximity to employment [was] obviously” one factor that created these islands of the poor. See Galbraith, The Affluent Society 248-49 (3rd ed., 1984).

[34] Galbraith, supra note 31, at 292.

[35] Id. at 293.

[36] In both the second edition of his ground-breaking book, which appeared in 1969, and the third edition, published in 1984, Galbraith advocated a guaranteed income or negative income tax “as a matter of general right and related in amount to family size but not otherwise to need,” in addition to public investments and expanded unemployment allowances. He explained that the idea had seemed utterly impracticable to him in 1958 but appeared reasonable later. See Galbraith, supra note 31, at 266-267 (2nd ed., 1969) and Galbraith, supra note 31, at 228 (3rd ed., 1984).

[37] Id. at 289-290.

[38] Id. at Chapter XXI, “The Divorce of Production from Security.” In later editions of The Affluent Society, beginning with the second edition in 1969, Galbraith argued for un-linking production and security especially for “those whom the modern economy employs only with exceptional difficulty or unwisdom.” He did not propose that the government create jobs for such people or attempt to encourage private employers to hire them: “Beyond a certain point,” he argued, “and given the shortage of qualified workers that will exist, it is impractical to pull the uneducated, the inexperienced and the black workers into the labor force and into jobs.” He also found a range of people, including “women heading households,” whom he believed the government should sustain economically rather than seek to employ. The Affluent Society, 266 (2d ed. 1969) and 227 (3d ed. 1984).

[39] Harrington, supra note 25, at 12-13.

[40] Id. at 12.

[41] This is virtually the same as Oscar Lewis’s idea of the culture of poverty, which he developed for explaining the resistance of some Mexicans and Puerto Ricans to economic growth and modernization. Lewis had not yet, by 1962, when Harrington’s work appeared, applied the idea to the poor minority within the United States. See Oscar Lewis, The Children of Sanchez (1961); Lewis, La Vida: A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of Poverty - san Juan and New York (1966); Lewis, The Culture of Poverty Scientific American 215 (1966): 19.

[42] Harrington, supra note 25, at 18.

[43] Id. at 129.

[44] Id. at 166. Historian Michael Katz points out the remarkable coincidence of such descriptions of poor people (and people of color) in the U.S. and in “underdeveloped nation[s],” and the most significant anti-colonial political movements and civil rights efforts of the twentieth century. “In the same years that social scientists described them as passive, apathetic, and detached from politics,” writes Katz, “all over the world previously dependent people were asserting their right to liberation.” See Michael B. Katz, The Undeserving Poor: From the War on Poverty to the War on Welfare 36 (1989). Particularly remarkable were passages in which Harrington compared the poor in the United States with the poor of Asia, at the same moment that U.S. engagement in Vietnam was increasing steadily. “Like the Asian peasant,” Harrington wrote, “the impoverished American tends to see life as a fate, an endless cycle from which there is no deliverance.” See Harrington, supra note 25, at 170.

[45] Dwight Macdonald, Our Invisible Poor, The New Yorker (January 19, 1963), in Poverty in America 6-39 (Louis Ferman, Joyce Kornbluh, and Alan Haber, eds., 1968).

[46] Katz, supra note 44, at 82.

[47] Macdonald, supra note 45, at 16.

[48] Id. at 20.

[49] Id. at 10.

[50] Id. at 23-24.

[51] This language calls to mind that from the 1980s of sociologist William Julius Wilson. In The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, The Underclass, and Public Policy (1987), Wilson, like other “underclass” researchers, attempted to justify state action on behalf of poor people by insisting upon their social aberrance and relative resistance to behavioral incentives that worked for other portions of the population. For a similar view of the “underclass,” see Erol Ricketts and Isabel Sawhill, Defining and Measuring the Underclass, Urban Institute Discussion Paper (1987). The author worked with Ricketts and Sawhill at the Urban Institute while they wrote the paper.

[52] Macdonald, supra note 45, at 23. Macdonald was wrong to suppose that public schooling, even at the primary level, had always been a common fiscal obligation in the United States. For discussions, see Michael B. Katz, The Irony of Early School Reform: Educational Innovation in Mid-Nineteenth Century Massachusetts (1968); Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, Schooling in Capitalist America: Educational Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life (1976); and Ira Katznelson and Margaret Weir, Schooling for All: Class, Race, and the Decline of the Democratic Ideal (1985). Bowles and Gintis, and Katznelson and Weir, agree that schools were not always publicly funded, although they disagree about whether universal public schooling ultimately occurred because of employers’ demands or because of working-class demands.

[53] Macdonald, supra note 45, at 24.

[54] See Harrington, supra note 25, at 75; Macdonald, supra note 45, at 8, 11; Galbraith, supra note 38 (2d ed.), at 215-16, 266, and supra note 33 (3rd ed.), at 185, 227.

[55] On links between civil rights and economic rights, see Kornbluh, supra note 12; Thomas Jackson, From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the struggle for economic justice (2006); Charles Hamilton and Dona Cooper Hamilton, The Dual Agenda: the african american struggle for civil and economic equality (2000).

[56] The Birmingham Truce Agreement, May 10, 1963, in The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader 159-60 (Clayborne Carson, David J. Garrow, Gerald Gill, Vincent Harding, and Darlene Clark Hine eds., 1991).

[57] James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 482-85 (1996). For a greater focus on economic inequality between whites and blacks, and the argument that civil rights laws and court-based strategies were “too little, and too late,” see John Lewis, Original Text of Speech to Be Delivered at the Lincoln Memorial, in The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader, supra note 56, at 163-65. For a contemporaneous observation of the March that was sensitive to its attention to black poverty as well as to statutory civil rights, see I.F. Stone, The March on Washington, in A Nonconformist History of Our Times -- In A Time of Torment, 1961-1967 122-24 (1967).

[58] Martin Luther King, Jr., I Have A Dream, in Negro Protest Thought in the Twentieth Century (Francis Broderick and August Meier eds, 1965), 404.

[59] Id. at 401.

[60] Friedman with Friedman, supra note 17, at 4.

[61] Id. at 180.

[62] Id. at 178.

[63] Moynihan, supra note 16, at 50. Friedman and Stigler also saw the negative income tax as an answer to such New Deal interferences with employer prerogative as the minimum wage. See Stigler, supra note 24, and discussion in Katz, supra note 44, at 104.

[64] Friedman with Friedman, supra note 17, at 192.

[65] Id. at 194-95.

[66] West Virginia was pivotal because it was the place where Kennedy proved to the national Democratic Party establishment that he could win large numbers of Protestant votes. Kennedy also demonstrated that he could win some Southern votes. See Theodore White, The Making of the President, 1960 114-37 (1961). One specific issue Kennedy addressed in West Virginia was the narrowness of the surplus food program, the expansion of which he made the subject of his first executive order. See discussion in Moynihan, supra note 16, at 117.

[67] On the initial cautiousness of the Kennedy Administration, and the political forces that made him cautious, see Allen Matusow, The Unraveling of America: A History of Liberalism in the 1960s 30-59 (1984).

[68] On the Area Redevelopment Act of 1961, see Walter Trattner, From Poor Law to Welfare State: A Social History of Welfare in America 292 (4th ed. 1989); James Patterson, America’s Struggle Against Poverty 127-29 (1981), Matusow, supra note 68, at 100-02.

[69] For the theory, see Richard A. Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin, Delinquency and Opportunity: A Theory of Delinquent Gangs (1960). On President Kennedy’s efforts in the area of juvenile delinquency, see Matusow, supra note 68, at 110-19.

[70] On the legislative priorities of the early Johnson Administration, see Michael Beschloss, ed., The Lyndon Johnson White House Tapes 24-149 (1997). The tax cut and the civil rights bill were two pieces of legislation left by Kennedy at the time of his death. Johnson pursued the tax cut aggressively in part to reassure Wall Street after the death of the President, as well as to warm business people and middle-class constituents to his administration.

[71] However, Burke and Burke, supra note 16, at 16, claims that a report produced within the Department of Health, Education and Welfare in 1964 (and not published until 1966) called for a version of an income guarantee.

[72] Id. at 18-19. Burke and Burke note that Sargent Shriver, head of the Office of Economic Opportunity [hereinafter OEO], expressed support for the negative income tax idea in October, 1965.

[73] Id. Moynihan, supra note 16, at 195, notes the support particularly of economists within OEO for the negative income tax.